Highlighting Bias and Misinformation from Psymposia and its Supporters

Who is the team determined to crush current efforts to legalize MDMA for PTSD?

Have you been following the drama around MDMA, Lykos and the FDA Advisory Committee hearing / ICER Report? If so, you know that very serious allegations were thrown at everything by a vocal group of dissenters during an extended public hearing portion of the Committee’s meeting. Several of the dissenters are either affiliated with the so-called “industry watchdog” group Psymposia, or have close professional relationships with members of that group, namely Neşe Devenot, Brian Pace and Russell Hausfeld (all affiliated with Psymposia), and Sasha Sisko and Kayla Greenstien (unaffiliated officially but close with Psymposia members and share the same agenda).

While Psymposia has raised some good questions and issues in the past and even in the hearing itself, the group’s strategy of bullying, pushing completely biased agendas and information, and outright falsifying information, along with their mission to take down MAPS / Lykos, discredits any of the legitimate issues they bring to the table.

Reliance on Lies, Hearsay, and Anonymous Statements

They use the false argument that they are protecting people who come to them from retaliation and dangle statements that position them as the only holders of the truth. There is no way to confirm or deny these accounts and this “new information” mentioned has not been shared.

MAPS/Lykos has an established process for reporting concerns and filing complaints. A review panel has thus far found no evidence of misconduct in any instances mentioned in the Advisory Committee hearing.

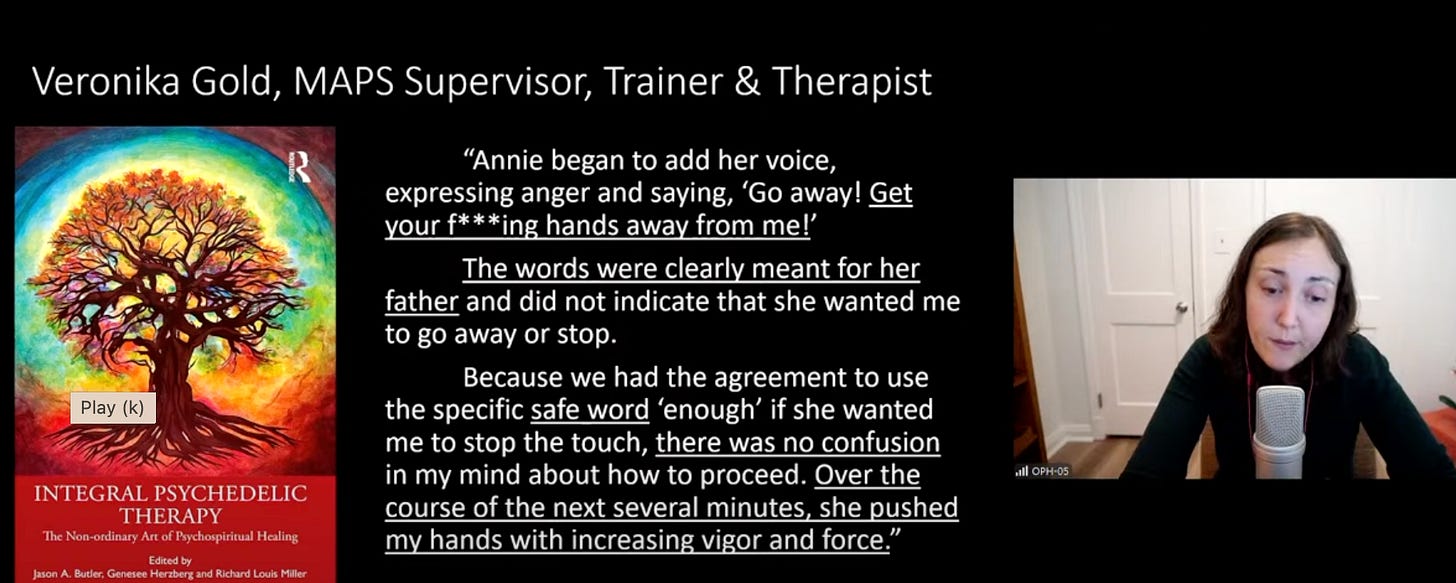

In the below slide, excerpted from the book pictured, Devenot fails to note that this was a ketamine-assisted therapy session (not MDMA) and takes the example completely out of context to fit their agenda:

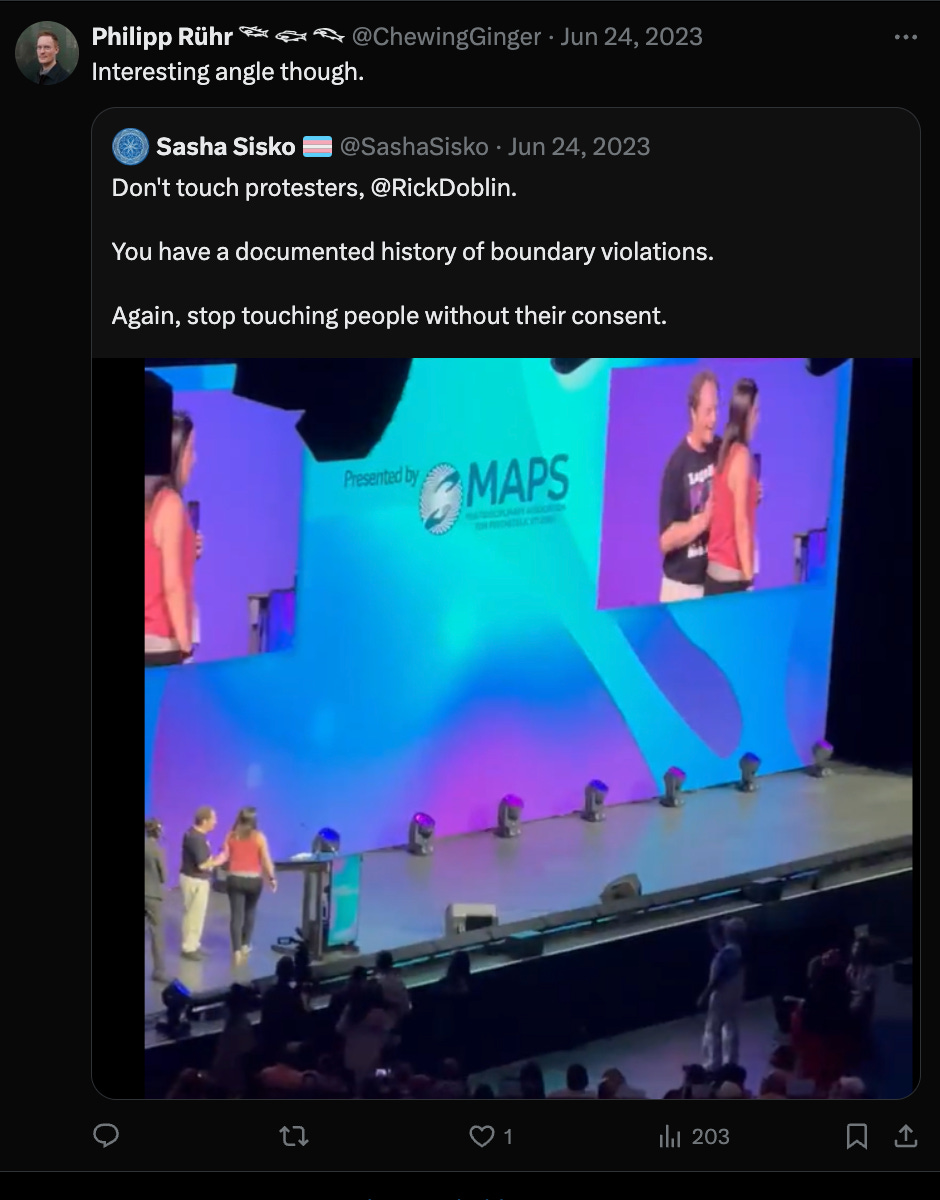

In the below slide, all tapes were reviewed and this event did not happen. I have learned the therapist was fully cleared by a review board:

Devenot’s most recent posts have begun to feel desperate and fail to include any specific provable details.

These posts say contradicting things about the FDA (the FDA doesn’t know everything; that the FDA is ignoring information sent their way)

Here Devenot reposts themself, presumably to increase engagement with their own post, and makes character judgments about the people “on the wrong side of the truth”:

Bullying and Personal Attack/Intimidation

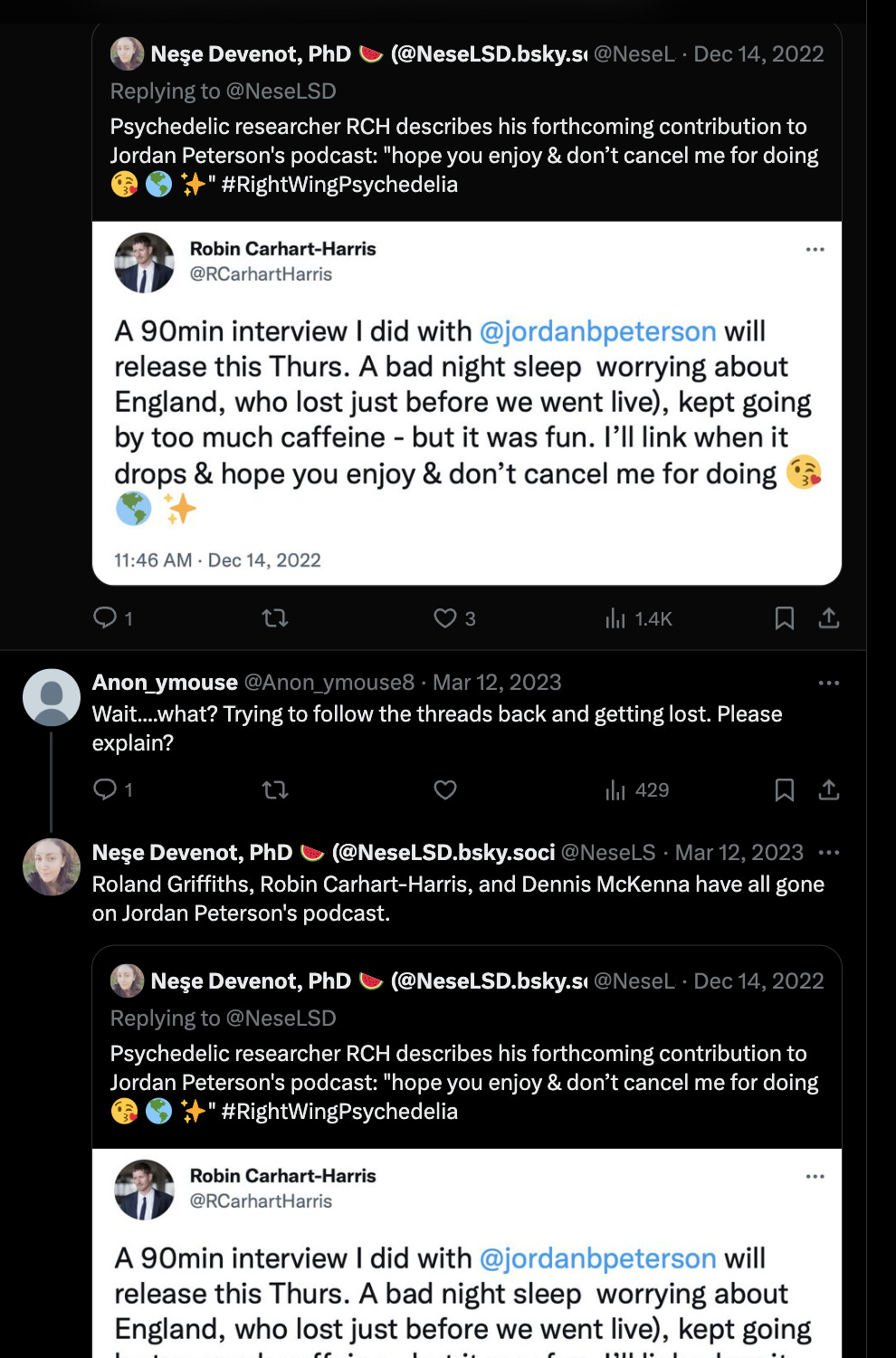

They are notorious in the psychedelic world for bullying and attacking scientists, researchers, business and nonprofit leaders, and others in the field, something which they accuse others of doing to them. Proponents of cancel culture, they have singled out people and organizations over the years to publicly abuse while representing themselves as standing up for people who fear retaliation from MAPS/Lykos and other groups.

Echo Chamber Tactics

Devenot, Pace, Hausfeld, Sisko and Greenstien continuously engage with each other, co-author work, repost each other and reference each other, creating a sense that there are many voices when in fact it’s an echo chamber. In the Advisory Committee hearing, they did not disclose their relationships to one another or, for at least 3 of them, their connection to Psymposia. They gave the sense of being many voices united and are hiding the truth—they have organized the effort to take down rescheduling MDMA and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.

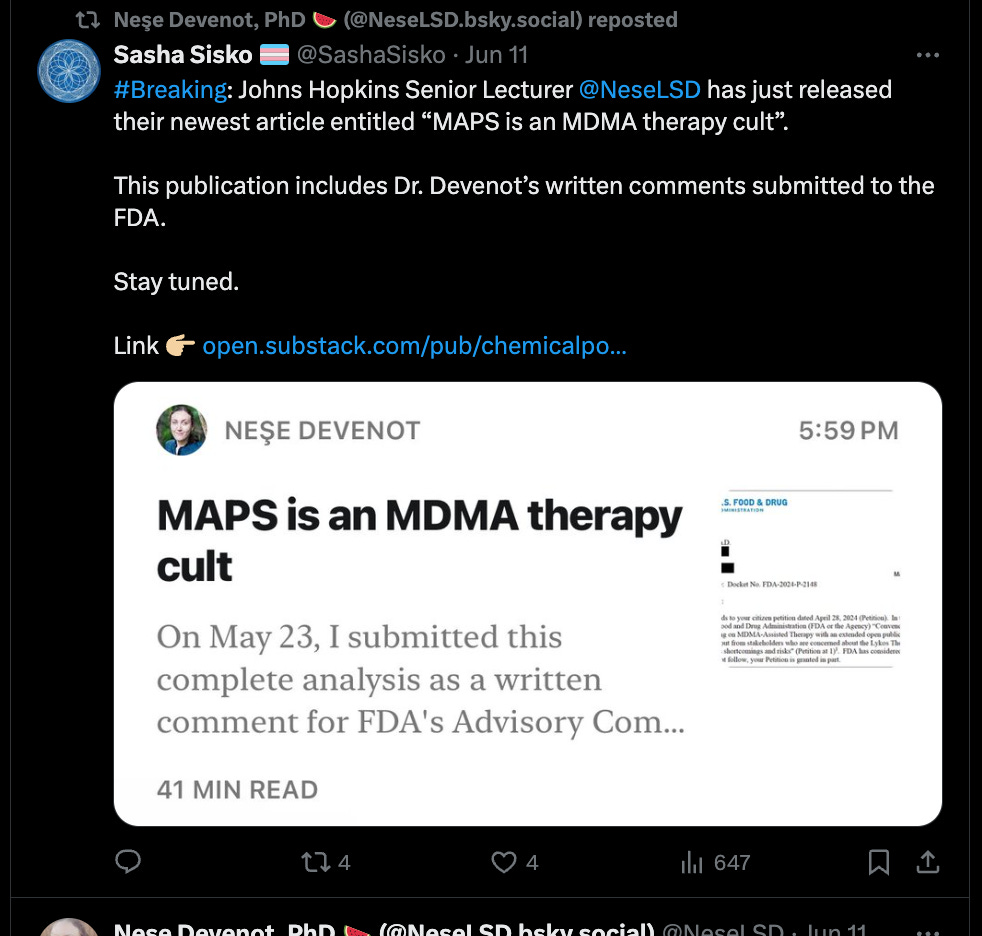

Pushing the False Claim that MAPS is a Therapy Cult (Twitter/X)

They also push the untrue idea that MAPS is a “therapy cult,” a point used to create drama in the Advisory Committee hearing. This sensationalized language, which Devenot claims “isn’t sensationalizing,” is meant to strike fear and uncertainty in the minds of people they present themselves as an “expert” to.

Cancel Culture Tactics

Along with attacks on individuals, they are pro “cancelling without redemption” of people with past transgressions.

Looking for the Spotlight

Devenot describes the talks they give on taking down MAPS/Lykos as “psychoactive” because of how they engage and excite people. Many posts afterward are self-congratulatory, revealing the rush that they get from “speaking truth to power,” which is actually misrepresenting the truth.

SXSW recap: Counter-Narratives for the Psychedelic Status Quo

Excerpts

I could also hear it, since I kept being interrupted by spontaneous cheers and applause.

That electricity was an effect of speaking truth to power.

After the panel ended, one person had to pause while they were midway into asking me a question. They apologized for physically shaking slightly, since they’d been so affected by the panel discussion. It reminded me of each of those previous conference presentations, when some people were noticeably buzzing when they walked up to ask me a question. I could have sworn that I caught a few slightly dilated pupils.

For some portion of the audience, it’s like the talks themselves are psychoactive.For example — I received this email afterwards, which speaks to the feeling of energy in the room:

“You're saying important things that are resonating with people, and it was amazing to feel the surge of heartfelt emotion from the audience reacting [to] you. [...] I’m viscerally appreciative of many of the things you're sounding the alarm about. Let me know if I can be of service in the future.”

As another example — a friend forwarded some “live tweets” from a group chat, which included these:

I can’t [record] everything she says haha but 🔥🔥🔥

Subtweeted Rick [Doblin] for putting Ben [Sessa] on a slide 💀

“We don’t need the medical model. Psychedelics weren’t going away.”

“There is a psychedelic guiding industrial complex. I reject it.”

I really should be videotaping all this it’s amazing

“Real relationality with indigenous groups requires dismantling capitalism”

She’s burning down the room it’s amazing. [...] I can barely get 1 quote in 10

Psymposia’s Response to Heroic Hearts’ Pharma-Backed Press Conference

https://www.psymposia.com/magazine/heroic-hearts-mdma-ptsd-veterans/

Excerpts from the above linked article showing lack of evidence and speculation

Yesterday’s Heroic Hearts press conference was meant to be a grassroots show of force. Sadly, what the organization and congressional leaders didn’t disclose was that their effort is funded by backers of Lykos Therapeutics, a therapy cult with a reported and documented history of cover-ups, data manipulation, and egregious psychological, financial, and sexual exploitation.

Problems with Scholarship

Devenot and Pace have collaborated on articles in academic journals (many from the same special issue) where they express the same bias and misrepresent or misconstrue evidence, or leave it out. Many articles feature interesting rhetorical analysis, but not rigorous science or bioethics, and rely heavily on anecdotes. They condemn psychedelics outside of community or Indigenous contexts and call for resistance as the only solution.

While Devenot represents themself as an expert in bioethics, as an early-career academic with a PhD in literature, they do not have the years of expertise in bioethics that might be assumed and have just taken their first full-time academic position after several fellowships.

Pace, another early-career academic, is a lecturer in the Department of Plant Pathology at The Ohio State University.

Excerpts from academic articles:

Psychedemia: Charting the future of interdisciplinary Psychedelic Studies Introduction to the Special Issue, Neşe Devenot, Brian Pace, Jason Slot, Alan K. Davis (Journal of Psychedelic Studies 7 (2023) S1)

In this issue, James Davies, Brian Pace, and Ne se Devenot extended this research to argue that psychedelic hype (Yaden, Potash, & Griffiths, 2022) works to mythologize, market, and institu- tionalize psychedelic-assisted therapy to fit a neoliberal medical paradigm that prioritizes profit over human well-being. Despite exuberant predictions that the broadscale application of P-AT will represent a sea change for mental health, they propose that narratives promoting P-AT nevertheless enact the same profit-maximization tactics that have been associated with undesirable outcomes for traditional pharmaceuticals. Further, they state that “corporadelic” actors are still positioning socially-determined mental distress as something best medicated, rather than as a signal for a necessary reorganization of society, despite claims that the approach is novel. As Davies explored in his prior research, powerful sociopolitical mechanisms have already undermined the effectiveness of SSRIs and other antidepressants by transforming mental and emotional suffering into that which is useful or nonthreatening to the status quo (Davies, 2022). Now, these authors argue, the same mechanisms are at work in the discourse of psychedelic medicine. Among these mechanisms, they posit that “depoliticization” protects the economic order from critique by offering P-AT as an antidote to its destructive mental health externalities. The authors propose that like SSRIs before them, market forces and private interests are in the process of “productivizing” psychedelics in a manner that helps capitalism run more smoothly, with the hyped rhetoric around microdosing and career-centered vision quests idealizing habits and activities that yield productivity and profit (i.e., “grindset”). The flipside of this, they argue, has been the effort by advocates of P-AT to exorcise the weird from psychedelics, pathologizing recreational use as frivolous and wasteful at best, if not outright dangerous. They infer that psychedelic hype has grown to hyperbolic pro- portions by mythologizing its powers to take patients on a heroic journey of personal salvation, which ultimately deemphasizes collective action. The authors warn that environmental determinants of mental distress cannot be medicated away and will not be fixed one P-AT session at a time. Instead, they propose that collective organization to build a more livable world would improve people’s mental health far more than normalizing a few dosed sessions with a therapist.

TESCREAL hallucinations: Psychedelic and AI hype as inequality engines, Devenot (Journal of Psychedelic Studies 7 (2023) S1)

By treating individual symptoms rather than calling for societal reorganization, the medicalization of psychedelics is repeating the same neoliberal, for-profit approach to healthcare that contributed to the poor outcomes of Prozac and other SSRIs. As a result, there is every indication that the transplantation of this approach into the novel context of psychedelic medicine will lead to similarly disappointing outcomes.

This methodology and its findings contribute to a developing subfield of critical psychedelic studies that interrogates the political and economic implications of psychedelic medicalization. Although industry insiders have positioned psychedelics as solutions for civilizational threats including political polarization, the rise of fascism, environmental degradation, and increasing rates of mental illness, scholars in other fields have associated all of these problems with rising inequality in society.

Rather than addressing the systemic drivers of these interrelated problems, major funders are explicitly building the psychedelics industry to extract wealth for ever-widening inequality. In this paper, I will argue that this counterfactual approach to mental healthcare is propelled by an elitist worldview that is widely-held among Silicon Valley’s billionaires.

As in the case of AI hype, industry leaders are arguing that psychedelics offer a profitable solution to the ravages of inequality without changing society’s underlying materialconditions. Rick Doblin—founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS)—has repeatedly stated that psychedelics “will be a catalyst for mass mental health” through their capacity to change individual perspectives (Doblin, 2021). While international media outlets have tended to run this line without further elaboration, Doblin clarified his meaning in a 2020 podcast, when he identified “mass mental health” with a “mass spiritualization” of humanity. According to Doblin, the psychedelic experience is “the antidote to genocide, to the holocaust, to nuclear destruction, to racism.... I see the medicalization [of psychedelics]...as a tool to bring about mass mental health or mass spiritualization you could say.... I see that what we need to do with psychedelics is expand our humanity” (CIIS Public Programs Podcast, 2020). Doblin further defines this spiritualization as a shift from literal or “fundamentalist” religious beliefs to a spiritual mysticism rooted in unitive psychedelic experiences (PSYCH, 2021, 39:53). This confidence in the notion that psychedelics will radically minimize interpersonal harms reappears in another frequent slogan: “I believe that fully globalized access to MDMA-assisted therapy can lead to a world of net-zero trauma by 2070” (Doblin, 2023). These claims are based on theological beliefs rather than medical evidence, and Doblin’s suggestion that psychedelic experiences necessarily encourage prosocial behavior is contradicted by both cross-disciplinary research (Pace & Devenot, 2021) and by the harms caused within MAPS’s own clinical trials (McNamee, Devenot, & Buisson, 2023; Nickles & Ross, 2022).

Instead of addressing these structural issues, Silicon Valley’s multinational corporations are exacerbating the inequality and precarity that are driving widespread distress. These corporations rely on a global, anonymous workforce of precarious and underpaid workers to process (or “annotate”) the large-scale data sets that enable their various AI systems, ranging from chatbots to e-commerce behavioral analytics to self-driving cars. The pay provided for this challenging yet tedious work is variable and unpredictable, since companies continually shift their outsourcing to regions with the cheapest labor force. The result is “a vast tasker underclass” (Dzieza, 2023) that exploits refugees and other “victims of economic collapse” in order to build systems that maximize profits through widespread immiseration.

To prevent psychedelics from becoming yet another extractive industry, we need to organize beyond the hubristic fantasies of the elite’s TESCREAL hallucinations. Any genuinely prosocial applications of either AI or psychedelics will depend on collective resistance to their conscription by neoliberalism and colonialism. The alternative is complicity in their use as technologies of elite persuasion.

Beyond the psychedelic hype: Exploring the persistence of the neoliberal paradigm, Devenot, Pace, and James A. Davies (Journal of Psychedelic Studies 7 (2023) S1)

Background and Aims: Advocates of psychedelic medicine have positioned psychedelics as a novel therapeutic intervention that will solve the mental health crisis by liberating individuals from their entrenched habits and limiting beliefs. Despite claims for novelty, the psychedelics industry is engaging in the same profit-oriented approaches that contributed to poor clinical outcomes with SSRIs and other earlier pharmaceuticals, which threatens to undermine their purported clinical benefits. Methods: We present evidence that the liberatory rhetoric of psychedelic medicalization promotes neoliberal, individualised treatments for distress, which distracts from collective efforts to address root causes of suffering through systemic change. Drawing examples from the psychedelics industry, we illustrate how the discourse of psychedelic medicalisation subjects socially-determined distress to psychotropic intervention through the mechanisms of depoliticisation, productivisation, pathologisation, commodification, and de-collectivisation. Results: Rather than disrupting or subverting the psychopharmaceutical status quo, the psychedelic industry’s current instantiation aligns with and upholds key facets of neoliberal ideology by adhering to the same facilitative mechanisms that scholars identified in the antidepressant industry. We identify these common mechanisms in examples unique to the psychedelics industry, including the search for psychedelic analogues and political lobbying to reschedule psychedelics. Conclusion: We demonstrate how a neoliberal mental health paradigm that individualises and interiorizes mental distress cannot meaningfully resolve suffering with ubiquitous origins in the current sociopolitical environment, which is characterised by inequality, precarity, exploitation, and ecological collapse. As a result, psychedelics must decouple from neoliberal incentives, and demonstrate efficacy, if they are to facilitate durable improvements in well-being and prosocial outcomes.

Proponents of psychedelic medicalisation are explicit that appealing to medical authority is a crucial component of a mainstreaming project that seeks to leverage trust in medical expertise to achieve psychedelic destigmatisation, cultural legitimacy, and eventually, broad legalisation (Entheogenesis Australis, 2018). Yet medicalisation will necessarily result in outcomes that depart from those associated with the extant, diverse Indigenous and countercultural community models for psychedelic use Further, the institutionalisation required to manufacture a professionalised Psychedelic- Assisted Therapy (P-AT) requires that it be standardised, profitable, and scalable above other considerations, and its equation of responsible use with medical monitoring may restigmatise and diminish non-pharmaceutical use, including among the very traditions that developed core knowledges and practices (Gerber et al., 2021; Noorani, 2019).

Griffiths clearly states his belief that P-AT should not address systemic drivers of mental distress, meaning those drivers that could be addressed by policy shift, institutional change, or restructuring of social relations. To the contrary, Griffiths argues that the re-association of psychedelics with medical authority will help ensure that institutions invested in maintaining the current hegemonic order are not chal- lenged. This is a strategy of ‘depoliticisation’—namely, the process by which suffering is conceptualised in ways that protect current economies from criticism (i.e., reframing suffering as rooted in individual rather than social causes, thereby favouring self over social reform). The abundant examples of depoliticisation in contemporary society include, for instance, the rapid proliferation of mental health workplace consultancies over the last 10 years, which have deployed mental health tropes to reframe growing population-level worker dissatisfaction and under- productivity as requiring specialist mental health framing and intervention (Davies, 2022; Frayne, 2015, 2019).

In other words, once widespread suffering has been medicalised and pathologized, large swathes of the population must now be treated, and the treatments generally preferred in the neoliberal era have been psycho-pharmaceutical. .

As with the creation of the DSM, the psychedelic industry is building systems to optimise the generation profits rather than providing the best care. The two main contenders for psychedelic-assisted therapy, MDMA and psilocybin, are both multi-hour commitments with co-therapist teams—a considerable expense. In pursuit of cost-cutting, explicit efforts are underway to modify psychedelic compounds to have shorter durations of action (Yakowicz, 2021).

To avoid replicating the mechanisms that have put economic outcomes above clinical benefit in the neoliberal era, the psychedelic movement must understand its structural accordances with the wider aims of capital and capitalism. The salvationary and utopian rhetoric and logics of psychedelic discourse bury beneath a “liberatory” veneer the same medicalising, pathologising, depoliticizing, commodifying, individualising, and de-collectivising dynamics that enabled psychophramaceuticals to become the governing emotional technology of the neoliberal era. Insofar as psychedelics may merely repeat and reaffirm these very neoliberal dynamics, they may do nothing at all to counter—at a structural level—the central drivers of distress. Instead, they may become—as their forebears— an instrument of neoliberal hegemony, facilitating the conditions of increasing inequality while distracting in- dividuals from attending to the root causes of their distress.

The belief that P-AT represents a paradigm shift in mental health does not make it so. Political violence, structural oppression, workplace exploitation, social isola- tion, inequality, social injustice, ecological collapse, and climate catastrophe are all significant social and environ- mental determinants of distress that cannot be fixed with individual solutions. If P-AT is deployed into the existing neoliberal mental health paradigm, mental distress will continue to be framed as a problem of mindset, ineffective coping, and inadequate resilience. While, for some, P-ATs might provide respite from suffering and potentially yield personal insights, those insights are not automatically the catalyst to change in material relations—which impact the lives of everyone—as their most ardent supporters extol psychedelics to be. As has ever been the case, material conditions can be more effectively addressed through collective organisation and co-ordinated action against exploitation and inequality. In the absence of such collective action, psychedelics may only exacerbate the very problems that the field is claiming to solve.

Dark Side of the Shroom: Erasing Indigenous and Counterculture Wisdoms with Psychedelic Capitalism, and the Open Source Alternative or, A Manifesto for Psychonauts, Devenot, Trey Conner, and Richard Doyle (Anthropology of Consciousness Vol 33 Issue 2, 2022)

While prominent psychedelic psychiatrists and behaviorists are focused on rooting out and transforming individual habits of mind, we argue that there is another, latent potential for psychedelics to draw attention to—and transform—the invisible, hegemonic infrastructures and ideologies that subtly naturalize and perpetuate deeply unequal societies.

In a nutshell, the Dark Side of the Shroom algorithm works like this:

Establish the technoscientific “legitimacy” of ancient plant medicines curated by Indigenous and counterculture traditions by ignoring the knowledge and sacred context and occasions of those traditions, as well as the history of psychedelic science.

Ignore the effects of set and setting—e.g., cultural context and ritual— and focus on what can be isolated and owned. Declare a “new psychede- lic science.” We point to the Mazatecs and Andean curanderismo, and the open source psychedelic science of Alexander and Ann Shulgin as well as researcher Roland Fischer, as examples of each respective type. For Fischer and the Shulgins, there was no “new psychedelic science,” only ongoing and courageous psychedelic science through the long prohibition—a lockdown aided and abetted by these very same institutions now declaring a brave New Jerusalem of psychedelic medicine.

Shift from the “sacred” context to the “medical context.” Avoid, elide, and ignore the “ego death” context of psychedelic experience and emphasize the

treatment of symptoms that correspond to dubious taxonomies (e.g., DSM).

Engage in high-profile media campaigns declaring the “new psychedelic science,” beginning with major publishing houses and gatekeeper periodi-

cals (e.g., Allen Lane, The New Yorker).

Project and protect exclusive rights to these knowledges. Pollan: “Not so

Fast on Psilocybin Mushrooms” (New York Times).

Raise millions by leveraging these new narratives of legitimation and desacral-

ization enabled by this “new psychedelic science.” Promise “to end the mental

health crisis” with this new intellectual property (Costa and Shead 2021).

Begin integrating psychedelics into mental health therapies with little to

no training.

Repeat.

We call for the “letting go” of monopolistic competition with a Fair Trade and open source approach to intellectual property (akin to the role of Linux and Apache for the emergence and sustainability of the Web) and a correlative collective DIY approach to ecodelic healing, which is already and even now explored in diverse ceremonies across the planet.

There is no evidence that this standardization and routinization of psychedelic therapy confers therapeutic benefit to individuals, since there is not a single, “correct” way to safely and meaningfully access psychedelic states of consciousness. (It would make as little sense to try to standardize the sound- tracks for sexual experiences on a global scale.) To the contrary, this approach to “scaling” prioritizes corporate profits over participant wellbeing. Similar tradeoffs are also occurring on other levels of the corporate medical paradigm, with demands for “cost-effective interventions” that include minimizing the amount of training required for therapists or guides; minimizing patients’ physical access to therapists or guides by relying on telemedicine and virtual reality interfaces; and reducing the total number of dosing ses- sions (Noorani 2020; Ponieman 2021)

Throughout this piece, Pollan seeks to naturalize as “sober” and “healthy” the specific avenues to psychedelic access that are most compatible with the existing, neoliberal capitalist order of society (Gearin and Devenot 2021). Emphasizing the transformation of the individual within an unchanging hier- archical order, each of his three proposed models offer a means of enriching and prioritizing the goals and preferences of a new psychedelic elite, whether the hierarchy is disciplinary (emphasizing scientific ways of knowing at the expense of other fields), eclesiastic, or corporate. His “neutral,” “evidence- based” vision is also deeply biased by class-blindness.

Right-Wing Psychedelia: Case Studies in Cultural Plasticity and Political Pluripotency, Devenot, Pace (Frontiers in Psychology December 2021, Volume 12)

Recent media advocacy for the nascent psychedelic medicine industry has emphasized the potential for psychedelics to improve society, pointing to research studies that have linked psychedelics to increased environmental concern and liberal politics. However, research supporting the hypothesis that psychedelics induce a shift in political beliefs must address the many historical and contemporary cases of psychedelic users who remained authoritarian in their views after taking psychedelics or became radicalized after extensive experience with them. We propose that the common anecdotal accounts of psychedelics precipitating radical shifts in political or religious beliefs result from the contextual factors of set and setting, and have no particular directional basis on the axes of conservatism-liberalism or authoritarianism-egalitarianism. Instead, we argue that any experience which challenges a person’s fundamental worldview—including a psychedelic experience—can precipitate shifts in any direction of political belief. We suggest that the historical record supports the concept of psychedelics as “politically pluripotent,” non-specific amplifiers of the political set and setting. Contrary to recent assertions, we show that conservative, hierarchy-based ideologies are able to assimilate psychedelic experiences of interconnection, as expressed by thought leaders like Jordan Peterson, corporadelic actors, and members of several neo-Nazi organizations.

Although Silicon Valley’s interest in disruption differs from the overt violence of mass racial attack, the frequent result of market-based disruption is catastrophic upheaval for the marginalized communities. Corporadelic actors are currently folding psychedelics into a corporate ethos predicated on novelty and cognitive labor: from microdosing coders to ayahuasca business coaches, psychedelics are seen as shortcuts to divergent market insight in a globalized, neoliberal marketplace. Since billionaires are invested in preserving the status quo of massive wealth inequality, their enthusiasm for psychedelics suggests that this class of drugs is not inherently a solution for ameliorating the extensive harms caused by social inequality.

The argument for psychedelic medicalization is made in dollars and cents—MDMA for PTSD is projected to be more cost-effective (Marseille et al., 2020) and profitable than standard treatments. When articulating a broader vision beyond legalizing psychedelic therapy, psychedelic advocates frequently describe a strategy consistent with a Trojan horse theory of change: broader psychedelic use will catalyze geopolitical reconciliation and become the chemical feedstock of world peace. Most recently, MAPS Executive Director Rick Doblin advanced the hypothesis that the mystical experience could be used as “a tool of political reconciliation.”

Indeed, Doblin has been making similar claims for most of his career, having once proposed a project entitled “Shaping a Global Spirituality While Living in the Nuclear Age” (Klein, 1985) to the United Nations, which articulated such a vision. Doblin is far from the only psychedelic advocate making sweeping claims about the power of psychedelics to potentiate systemic change, rather than being assimilated and put to use by the current political and economic order (e.g., Peck, 2020).

Experiments or studies that have sought to explore whether psychedelics have a consistent impact on political ideology and psychedelic use have thus far failed to rule out lurking variables in participant set and setting. Researchers should be careful to avoid conflating single-issue beliefs with specific ideologies, since particular values (e.g., environmentalism) are represented across different political perspectives and shift over time. We discourage the use of underpowered studies to make broad claims, especially given the risk of exaggeration and distortion in the media, which can further influence patient expectation and researcher bias (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018). Because of the sensitivity of study participants to suggestion under the influence of psychedelics, it is crucial that researchers publish the manuals used in psychedelic therapy and describe any significant variation within the study of the therapeutic environment (e.g., the presence or absence of religious imagery) (Lattin, 2021). Since public relations campaigns, intake procedures, questionnaires, and preparatory sessions can all prime and influence participant expectations, which can in turn affect a study’s measured outcomes, we recommend the development of new standards for reporting on psychedelic clinical trials that include open publication of these materials (Petranker et al., 2020; Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2021).

Assertions that psychedelics induce a shift in political beliefs will have to address the many historical and contemporary cases of psychedelic users who remained authoritarian in their views after taking a wide variety of psychedelics or became radicalized after extensive experience with them. We propose that anecdotal accounts of psychedelics precipitating radical shifts in political or religious beliefs are common but result from factors relating to the set and setting and have no inherent directional basis on the axes of conservatism-liberalism or authoritarianism- egalitarianism. Instead, we draw from critical perspectives in the humanities and social sciences to argue that any experience which challenges a person’s fundamental worldview—including psychedelic experience—can precipitate shifts in political belief.

Whether on grounds of supporting the troops or following doctors’ orders, psychedelics—properly contextualized—are palatable to conservatives. In fact, themes of psychedelic authoritarianism within the context of medicalization go beyond the PR campaigns of organizations such as MAPS. Such authoritarian tendencies have appeared in clinical trials, underground contexts, and instances of state-sanctioned psychedelic torture (Nickles, in press).

Be warned: platforming these individuals and the Psymposia brand will result in continued spread of misinformation, bias, lies and ultimately harm.

See more images and excerpts here.

Reach out at amestallisker@proton.me